Question: how did Argentinian wine, so recently the object of pitying amusement from wine buffs, become profitable, fashionable and, more to the point, drinkable?

For the full, book-length answer to the above you’ll have to wait until January 2012, when American author Ian Mount’s The Vineyard at the End of the World is published. A blend of in-depth reportage, historical narrative and gossipy anecdotes, the book, the first of its kind in English, traces the rise, fall (in fact, multiple rises and multiple falls) and eventual triumph of the Argentinian wine industry.

For the price of a tostado (after all, it is his first book) The Real Argentina managed to snag an exclusive interview with Mount following his successful appearance at Buenos Aires’ annual book fair.

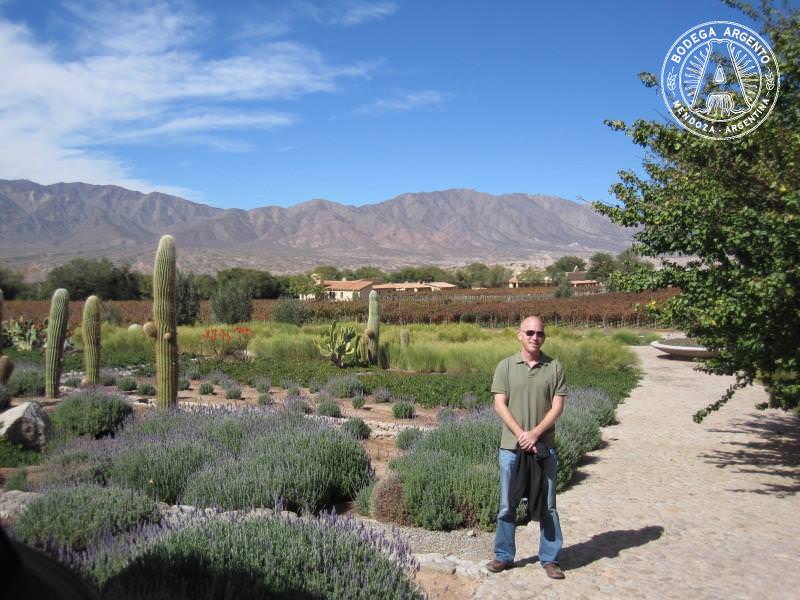

Photograph by Ian Mount

When and how did it occur to you that this was a story which needed to be told?

I wish I could say that it was some genius idea on my part, but it wasn’t. When I moved here with my wife Cintra in 2005, I was working as a freelance journalist. One day, Food & Wine magazine asked for a story on a Chilean wine family. Then they asked for one on Mendoza. Another story I wrote about Mendoza appeared in Fortune…. At some point along the way, somebody said, quite offhand, ‘You know, it’s a pity that there’s no good book about Argentine wine.’ And he was right. Here was this fascinating industry with great characters that was producing a wine that was booming in the US and Europe, and no one had written a serious book about it – certainly nothing in English. So I wrote a proposal, found an agent… and started drinking a lot of wine.

Ian Mount – Photograph by Justina Maíz Casas

You appear to have interviewed many if not most of the main players in the Argentinian wine industry. Who stands out in your memory and why?

One of the great things about the wine industry here is that almost everyone is incredibly generous with their time, not to mention honest and unguarded. Pedro Marchevsky, the former viticulturist at Bodega Catena Zapata, probably knows more about grape-growing than anyone I’ve ever met. The wine writer Miguel Brascó told me that he’s seen vines stand up at attention when Marchevsky comes round, just like rose bushes do around English gardeners.

I also had a great series of interviews with Paul Hobbs, the American consultant that Nicolás Catena brought on in the late 1980s to improve wine quality and make international-style wines. And of course I have to mention Catena himself, who was the first Argentinian winery owner to have both the foresight and the resources to push toward ‘international quality’ wines.

Oh, and if you were to ask me who had the best Hells Angels moustache, I’d have to say ex-Trapiche winemaker Ángel Mendoza.

That was going to be my next question. Putting facial hair aside – though not without some regret – if you had to choose the two people who did most to put Argentinian wine on the map, who would they be?

I’ll start with the obvious and then get less so. Everybody points to Nicolás Catena as the man who had the largest role in creating high-quality Argentinian wine for export. And they’re right. In the 1980s, Nicolás Catena realized that Argentina’s drinkers were drinking less and that if the industry were going to survive it was going to have to find other people—i.e. foreigners—to drink the stuff they were making. For that to happen, Argentinian winemakers were going to need to improve the quality of their wine and make it in an international style. Catena ponied up money for new equipment (barrels, presses, etc etc), hired consultants like the American winemaker Paul Hobbs to train his winemakers in the new style, and made Argentinian wine famous.

The other person I have to mention is the King of All Sideburns, Carlos Saúl Menem. When Menem and his economy minister Domingo Cavallo pegged the peso to the dollar and opened up the economy to foreign investment, it was like a sudden rush of oxygen hitting a fire: the wine industry exploded. The dollar/peso peg made imports suddenly cheap, so Argentinian wine makers could buy all the barrels and presses and so on that they couldn’t afford before. Now, the downside (and its upside). By allowing the dollar/peso peg to continue long after its sell-by date instead of letting the peso float, Menem helped bring about the 2002 crash and devaluation. That of course sucked for most Argentinians, but it was great for Argentinian winemakers who exported their wine.

Photograph by Ian Mount

Why do you think so many people are talking about Argentinian wine right now? Is ‘Malbec’ a viable one-word answer to that question?

Malbec is definitely one part of the equation, but it’s not the only part. The most important aspect of Argentina’s wine boom is what people usually call the price/quality ratio. Argentina’s grape-growing regions are warm and dry, which means there are few problems with pests and molds, so little need to buy pesticides, fungal treatments etc. Argentina’s other production costs (labor, grapes) are also generally low by international standards. Together, these low costs mean that Argentinian wineries can offer the same quality product for less money than other producers:

As for Malbec, it’s important to remember that the US is the biggest export market for Argentinian wine — over a third of the exports go there — and the yanqui consumer started to drink wine just as Argentinian wine came on the scene. Malbec was this yummy, fruity, dark, easy-drinking wine, great for a steak – and that’s what new American wine drinkers wanted. Those same newbies also are attracted by the unique and new, and Argentinian Malbec was certainly that. As time went on and Argentinian winemakers learned more about their land and the nuances of Malbec, they started making more complex wines. As they were doing that, the palates of new wine drinkers in the U.S. and beyond also grew more nuanced and complex. You could say Argentinian wine and American wine drinkers grew up together.

The Chileans are fond of saying things like, ‘Malbec is a fad’ and ‘The Argentinian wine boom is a bubble waiting to burst’, etc. Is there any truth to this?

I think that’s just wrong, to be honest. Of course, Argentinian winemakers will have to diversify beyond Malbec at some point. Malbec won’t be the “it” grape forever. The best way to increase Argentina’s palate, at least to me, would be to ride varietals that are uniquely ‘Argentinian’—Malbec, Bonarda and Torrontés—to success in the middle market, and use single vineyard Malbecs and Malbec-heavy blends at the high end.

But I’m not saying there aren’t potholes ahead, you know? Anybody who has lived in Argentina for more than a day knows that consistency and normality are not exactly the hallmarks of Argentinian life. An example: right now the top headline on the 24 news channel is ‘Ezeiza funciona con normalidad’ – it’s news that, for once, the country’s main airport isn’t screwed up.

Photograph by Ian Mount

Finally, if there was one thing you could change about Argentinian wine or the industry in general, what would it be?

This is going to sound sort of unpatriotic, but I really wish there was more imported wine here. I mean, don’t get me wrong, I love Argentinian wine as much as the next guy. But every f@ day? Last December, I went to the opening of the DiamAndes winery in the Michel Rolland-headed Clos de los Siete, and the winery’s owners served a white wine from their Bordeaux winery, Château Malartic-Lagravière. I almost fell off my chair (to be fair, the sheer amount of wine consumed might be responsible for that). I mean, it wasn’t that it was better than Argentinian wine, though it was amazing. It’s just that it was different. And variety is the spice of… well, you know where I’m heading with that.

For more information and some excellent photographs, check out Mount’s website.

Matt Chesterton

Latest posts by Matt Chesterton (see all)

- Top Chefs of New Argentine Cuisine - November 6, 2012

- Argentina at the London 2012 Olympics - June 12, 2012

- The Best Wine Tasting Venues and Events in Buenos Aires - February 16, 2012

Argentinian Malbecs vs. The World

Argentinian Malbecs vs. The World  Wine Tasting in Argentina: Interview with Three Top Sommeliers

Wine Tasting in Argentina: Interview with Three Top Sommeliers  Own Your Piece of the Dream – Vineyard Sharing in Mendoza

Own Your Piece of the Dream – Vineyard Sharing in Mendoza  Argentina Vineyard and Winery Tours

Argentina Vineyard and Winery Tours  Why Chileans are Investing in Argentinian Vineyards

Why Chileans are Investing in Argentinian Vineyards  A Look at Some of Argentina’s Most Expensive Wines

A Look at Some of Argentina’s Most Expensive Wines  AN ARGENTINE FIRST: BACKSTAGE AT THE CONTEST OF THE BEST SOMMELIER OF THE WORLD

AN ARGENTINE FIRST: BACKSTAGE AT THE CONTEST OF THE BEST SOMMELIER OF THE WORLD  Top 10 Curious Facts About Argentina Wine

Top 10 Curious Facts About Argentina Wine  A Taste of Terroir: Argentina’s Diverse Wines & Wine Regions

A Taste of Terroir: Argentina’s Diverse Wines & Wine Regions  450 Years of Wine in Argentina – A Potted History

450 Years of Wine in Argentina – A Potted History  The Endless Debate: Screw Cap Wine vs. Cork

The Endless Debate: Screw Cap Wine vs. Cork  The Best Wine Bars in Buenos Aires

The Best Wine Bars in Buenos Aires